Geneticist who unmasked lives of ancient humans wins medicine Nobel

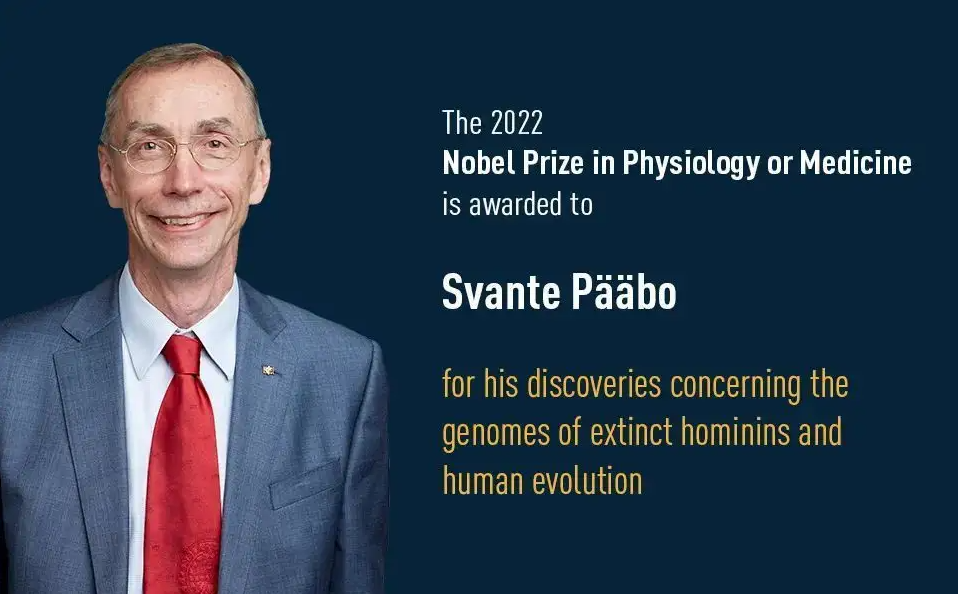

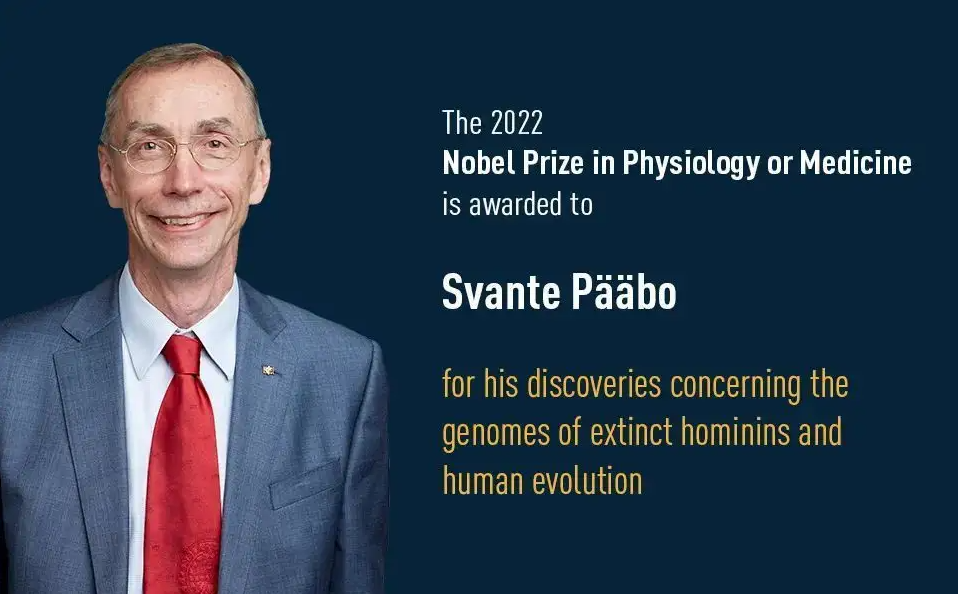

Svante Pääbo has been awarded a Nobel prize for discoveries about the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution.Credit: Alamy

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded for pioneering studies of human evolution that harnessed precious snippets of DNA found in fossils that are tens of thousands of years old.

The work of Svante Pääbo, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA) in Leipzig, Germany, led to the sequencing of the Neanderthal genome and the discovery of a new group of hominins called the Denisovans, and also spawned the fiercely competitive field of palaeogenomics.

By tracing how genes flowed between ancient hominin populations, researchers have been able to trace these groups’ migrations, as well as the origins of some aspects of modern human physiology, including features of the immune system and mechanisms of adaptation to life at high altitudes.

Damaged DNA

Pääbo had to develop ways of analysing DNA that had been damaged by thousands of years of exposure to the elements, and contaminated with sequences from microorganisms and modern humans. He and his collaborators then put these techniques to work sequencing the Neanderthal genome, which was published in 20102. This genetic analysis led to the finding that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens interbred, and that 1–4% of the genome of modern humans of European or Asian descent can be traced back to the Neanderthals.

Pääbo’s techniques were also used to identify the origins of a 40,000-year-old finger bone found in a southern Siberian cave in 2008. DNA isolated from the bone indicated that it was from neither Neanderthals nor Homo sapiens, but came from an individual belonging to a new group of hominins3. The group was named the Denisovans, after the cave in which the bone was found. Ancient humans living in Asia interbred with this group, too, and Denisovan DNA can be found in the genomes of billions of people alive today.

Health implications

Pääbo’s work teasing out DNA from Neanderthals, Denisovans and other hominins also has important implications for modern medicine. Although the proportion of the human genome comprised of archaic DNA is small, this material seems to punch above its weight, making an important contribution to the risks of diseases ranging from schizophrenia4 to severe COVID-195. And people living on the Tibetan Plateau can thank Denisovans for gene variants linked to high-altitude adaptation6.

“The fact that a good fraction of the people running around in the world today have DNA from archaic humans like Neanderthals is of important consequence to who we are,” says Reich. “So I think that knowing that and trying to understand the implications of that for health is something that will be with us for the rest of our time as a species.”

Viviane Slon, a palaeogeneticist at Tel Aviv University in Israel who did her PhD under Pääbo’s supervision, says her former mentor has an “uncanny” ability to see the larger picture while remaining laser-focused on details. When Slon was working on remains that turned out to be a first-generation Denisovan–Neanderthal hybrid, the sequence of maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA matched that of a Neanderthal. But, when publishing those results, Pääbo urged Slon to reserve judgment until they had sequenced nuclear DNA inherited from both parents. “He wouldn’t let me write that it’s a Neanderthal because we didn’t know that, and in fact it turned out to be a mixed offspring,” Slon says.

Reich says that working with Pääbo and the team he organized to sequence and analyse the first Neanderthal genome was inspirational. “It was the best consortium ever,” Reich says. “He recognized how special and unique this type of data they were producing was.” This eventually inspired Reich to set up his own ancient DNA laboratory.

Pääbo’s influence on ancient DNA work has been such that it’s hard to imagine where the field would be without him. “He’s the godfather of the field,” says Skoglund.

Nature 610, 16-17 (2022)